Claims Processes Should be Cooperative, not Adversarial

Rethinking the most important part of protection plans and insurance policies

Although the purpose of warranties, protection plans, and insurance policies is to offset financial risks (e.g., due to product defects, accidents, or unexpected events), poorly designed claims processes, apathetic customer service, and prioritizing profits over truth and understanding often undermine this purpose.

Recently, a study conducted by nonprofit research firm KFF found that the top problem for insurance customers was not affordability. It was the claims process. Nearly 60% of those surveyed said that they experienced problems, such as denied claims or failing to receive pre-authorization for medicine. In our view, this isn’t something that we should accept.

In this article, I’d like to make the case that adversarial claims processes are bad for everyone involved, and why designing a collaborative process is a worthwhile investment for a company that offers protection plans.

Adversarial Processes Determine Winners & Losers, not Truth

As a licensed attorney who spent nearly 4 years getting my law degree, one of the core ideas I was taught about our American legal system is that we rely on an adversarial adjudicating process. If two parties duke it out in court, each side gets a chance to make the argument that makes their case look as good as possible. Plaintiffs cherry pick facts to highlight how badly they’ve been injured. Defendants present well crafted stories to imply how the Plaintiff is lying, or rely on a curated set of cases to show how, legally speaking, the Plaintiff has no basis for a lawsuit.

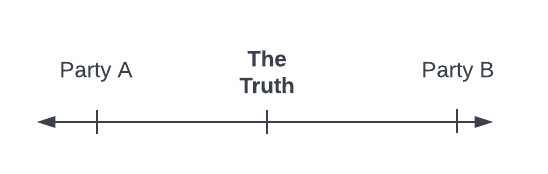

This process of presenting the best-sounding arguments from each side before an impartial judge was (and continues to be) considered by legal scholars to be a method of arriving at the truth. The idea goes that the judge hears two extreme versions of the story, and then assumes that the truth is likely somewhere in the middle.

If you’ve ever participated in a lawsuit or have been to trial, you know that this theory isn’t borne out in practice. The adversarial system encourages the parties to embellish their side of the story, bury or discredit factual evidence that undermines their case, and use arbitrary legal processes to achieve the outcome they want—not the outcome that each of the parties deserves.

The outcome of the [adversarial] process is not about arriving at the truth, it’s about deciding winners and losers.

Because of this system, the adjudication process ends up feeling much more like playing a game of Battleship rather than Guess Who—often ending with the parties either settling out of court before the truth comes out, or with one side winning because their lawyers told a more convincing story to a jury. The outcome of the process is not about arriving at the truth, it’s about deciding winners and losers.

Everyone Loses with Adversarial Processes

When claims processes are designed to be adversarial, everyone loses.

They create uncertainty for the customer

Unlike our legal system, claims processes don’t have an independent adjudicator. The company that sold you the warranty or policy also decides whether to approve or deny your claim.

This isn’t necessarily a bad problem, depending on what the priorities of the company are. If the company puts profits above all else, then paying out claims directly undermines that goal—causing an adversarial claims process to emerge, intentionally or unintentionally.

This creates an enormous amount of uncertainty for claimants. The onus is placed on the customer to make their case by providing evidence that proves:

that they complied with the terms of the agreement, and

that the event itself is covered under the agreement.

These requirements feel like barriers for the claimant that—if they aren’t overcome—would give the company an opportunity to deny a claim on a technicality. This reality makes the outcomes of adversarial claims processes notoriously uncertain for customers. You don’t have to look too hard to find examples of this uncertainty.

They cultivate poor work culture and apathetic employees

When the goal is to find ways to deny claims, companies cultivate a culture that treats their customers with contempt. Then, claims are an annoyance to be done away with and delayed as long as possible—ultimately making for a poor customer experience.

But it’s not only bad for the customer; it’s also bad for the company. Employees are pulled between trying to help upset customers, and not approving too many claims for fear of retribution. This fosters a negative work culture, which in turn makes it harder to recruit driven and talented people. Such a company won’t find problem-solvers…which is why it’s unsurprising that so many customers who file claims with these companies don’t have their problems solved.

They encourage the company to deceive its customers

When a company treats its customers’ claims like annoying obstacles to profit, then it naturally follows that the company will:

obfuscate the terms by putting the important stuff in the fine print;

avoid honest and unfiltered reviews from past claimants; and

describe their service in their marketing copy in a way that is misaligned with their terms and claims process

The sum total of these practices basically amounts to deception. And you can’t build a strong, lasting relationship based on deception.

They prevent the company from learning the truth of each case

Perhaps the most important downside of adversarial claims processes is that they tend to willfully disregard the truth. When your customer is your adversary, learning what honestly happened is immaterial. All that matters is whether the company is obligated to approve a claim (i.e., whether there is a substantial risk of the customer filing a complaint against the company if their claim is denied).

Why is this bad for the company? It prevents the company from gathering good data which would accurately reflect the risk of the event that they’re covering. If the company offers theft protection, then they don’t learn about the true theft rates—only how often they feel obligated to pay out.

If the risk of theft suddenly shifts (e.g., due to the proliferation of battery-powered angle grinders), or if a new player enters the market that offers a more innovative service, then such a company won’t have good data upon which to adjust their pricing or to uncover discounts. Tailoring the pricing based on a number of variables (or “parameters”) is what is sometimes referred to as parametric risk modeling, which is something that can only be achieved with granular and accurate data.

Everyone Wins with Cooperative Claims Processes

The Oxford Dictionary defines “cooperative” as:

involving mutual assistance in working toward a common goal

This is better for everyone involved in claims processes because it:

Fosters trust between the customer and the company

Builds a positive work culture with motivated employees

Encourages transparency by the company

Facilitates learning the truth of each case

This leads to happier customers, a better workplace, and company growth. And perhaps even more importantly, it results in acquiring good data that enables offering better and more affordable products and services over time.

In a future article, we’ll dive into how to design a cooperative claims process by (a) prioritizing truth over profits, and (b) building technology that makes gathering evidence almost effortless. And we’ll explain how we’re implementing a cooperative claims process for StableCare—a theft protection membership designed for e-scooters, e-bikes, and other emerging PEV categories.